The Placebo Effect

There is no more confusing term in medicine than “The Placebo Effect.” It is a single term that pretends to have a single definition but, in fact, describes a phenomenon that is multi-factorial. It refers to a variety of pharmacologically inert therapies that are effective for a variety of reasons.

Pharmacologically inert therapies:

(1). Sugar pills

(2). Petroleum jelly or fake creams

(3). Innocuous Inhalants

(4). Saline injections

(5). Fake medical devices such as ultrasound

(6). Sham surgery

(7). Acupuncture with retractable needles

(8). Intracranial electrodes that are in the off position

Reasons why pharmacologically inert treatments may be effective:

(1). The natural course of most illnesses is to improve.

(2). Patients often have a desire to please an authority figure so they often report exaggerated improvement when asked.

(3). Expectation of an improvement can cause a patient to think an improvement happened when none did.

(4). Unseen or unknown events can cause a patient to mis-perceive that something therapeutic has occurred.

(5). Unseen or unknown agents that are not under study can be responsible for the patient’s improvement.

(6). The power of suggestion can actually cause real brain changes that affect the body.

The placebo effect refers to all of these events. The problem is that these events are difficult to dis-entangle. Also, you probably have an observer bias towards anything referred to as a “placebo effect.”

Doctors and medical researchers perceive the placebo effect as a nuisance that they need to account for whenever they do a clinical trial. Patients think that placebos are fake treatments that an impatient doctor gives to a patient who is bothersome and/or naïve. Also, most people believe that deception and paternalism are essential elements.

I would like to suggest that there are only two categories of reasons that explain the placebo effect. The first category is mis-perception. Reasons one through five fall into this category. Mis-perception is easy to understand and is not terribly exciting.

The second category is more interesting. It involves a genuine change in brain function. There is real physiologic improvement in medical conditions. Reason number six falls into this category.

Wow! Now that is exciting.

However, you must understand one caveat. I am NOT saying that the placebo effect can “treat” any illness. It can only trigger a compensatory brain mechanism. For example, endogenous opioids for pain, adrenalin for fear or danger, Substance P to facilitate pain perception, Oxytocin to deal with the arrival of an infant, Dopamine to learn which environmental stimuli produce reward, histamine to trigger the inflammatory response, and so on throughout all the regulatory neurotransmitters and hormones. These compensatory mechanisms don’t treat disease. They are physiological responses to injury and insult. What I am saying is that you can initiate a physiological response through non-pharmacological means.

An example of this is when I tell you that you are wrong and you feel bad in your stomach. I have caused a change in your neurotransmitters through non-pharmacologic means.

Why don’t we change the definition so that it focuses on number two and excludes all the number ones? How about if we throw the term “placebo effect” in the trash can and create a new term. How about if we call it “Non-Pharmacological Intervention” or NPI?

Let’s re-consider some of the myths and biases. First of all, is deception absolutely necessary? Second, must a patient be bothersome or unintelligent in order to respond to NPI? Third, must a patient be naïve in order to respond? Finally, does there have to be paternalism or could there be collaboration between doctor and patient instead?

Wait a minute, if the new definition is “Non-Pharmacological Intervention,” won’t that include other therapies that don’t inject anything into the body? What about psychotherapy? What about hypnosis? What about acupuncture? Surely these are all forms on non-pharmacologic intervention. Right?

You might think at first glance that these therapies are too different to all be lumped together. However, what do you think are the essential therapeutic elements common to all these treatment modalities?

How about suggestion, expectation, and all the factors involved in the doctor-patient relationship?

Remember Dr. Freud? He started out with a thing called mesmerism (hypnosis) that he got from a French guy named Mesmer. Then, he morphed it into his famous “talking therapy” (psychotherapy). Dr. Mesmer started out with the idea that maybe he could make people better by simply telling them to get better. Sort of like the placebo effect, don’t you think? Is it really so hard to conceptualize that hypnosis and psychotherapy are just elaborate ways to achieve the placebo effect? Do you think we could include a few other things like acupuncture, magnetic therapy, or homeopathy in this category?

Actually, you probably reject this whole idea because I used the term “placebo effect.” Remember, you likely have some observer bias to that term. Let me ask it this way, “Is it really so hard to consider the possibility that the fundamental curative elements are the same across a wide range of non-pharmacologic interventions?

Have I made it an interesting enough question to get your attention?

With that last sentence in mind, I have an announcement. I decided to actually write a real scientific article. It will be a review article about non-pharmacological interventions. It will discuss functional neuro-imaging and how this technology is allowing us to actually see these interventions affecting the brain.

When I was researching the placebo effect in order to write this chapter, I became inspired to write a real review article that I could submit for publication. Understand that there will be none of the humor and colorful language that is so typical of something written by me. Instead, it will be a real peer-reviewed scientific article.

Feel free to provide feedback. What I really need is a better title. This title is OK but it is not exactly accurate and could be a little misleading. I have not been able to come up with a better one.

OK, here it is:

Non-Pharmacological Intervention (NPI)

A review of the effects of psychotherapy, hypnosis, placebos, and integrative medicine on brain function.

Abstract

The human brain is intimately connected to the environment through five sensory modalities whose information is processed chemically through a complex neural network. Therefore, events occurring in the environment can cause changes in the brain that can affect the body. There is a growing literature that is revealing the neurobiological mechanisms of non-pharmacological interventions to treat medical conditions. For example, some patients with pain, irritable bowel syndrome, major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and Parkinson’s disease who are treated with these interventions have cordance, blood flow, and metabolic changes in their brains that are associated with clinical improvement. It is important to determine the essential aspects of psychotherapy, hypnosis, placebos, and integrative therapies that best facilitate brain changes resulting in medical benefit. Since these interventions may not work to the same degree in everyone, it is also important to determine patient characteristics associated with clinical improvement. Finally, by using the term “Non-Pharmacological Intervention (NPI)” we hope to focus future research and incorporate these modalities into mainstream medical practice in a more appropriate way.

Introduction

Socialization factors affect your health. For example, people who are married live longer than people who are divorced and people who are divorced live longer than people who were never married. (Kaplan and Kronick) If your spouse becomes obese, then you have a thirty-seven percent chance of also becoming obese. If your best same sex friend becomes obese, then you have a seventy-one percent chance of also becoming obese. (Christakis and Fowler) People who attend religious services regularly tend to live longer. (Hall) (Schnall et al) Elderly individuals with the most extensive networks of good friends and confidantes outlive those with the fewest friends by twenty-two percent. (Giles)

It would appear that socialization factors affect longevity and obesity. These are gross measures of health and, therefore, any individual study might not be conclusive. However, there are multiple studies suggesting that socialization factors can have a positive effect on your health.

Can we determine the essential non-pharmacologic elements that have a positive health benefit?

There are several therapeutic modalities that have tried to capitalize on positive socialization to improve medical outcomes or treat specific conditions. Instead of using pharmaceutical agents, these modalities use things like doctor-patient relationships, expectation, cognitive paradigms, behavioral techniques, relaxation, trance, sugar pills, touch, massage, magnets, needles, etc. These approaches effectively treat certain conditions and are associated with neurobiological changes that can be seen on functional brain imaging.

Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy (CBT) and/or Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) can be effective treatments for major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and irritable bowel syndrome. (Gould et al) (Keller et al) (Weissman and Markowitz)

Hypnosis is generally thought to be ineffective in about five percent of people and maximally effective in about ten percent. Everyone else is on a sliding scale in between. (Carroll) Effectiveness may vary but a recent meta-analysis of adjunctive hypnotherapy with surgical patients found that patients in the hypnosis treatment groups had better clinical outcomes than eighty-nine percent of patients in control groups. (Montgomery) Also, hypnotherapy has been shown to be more effective than placebo in treating pain (Domangue et al), IBS (Whorwell et al.), and hypertension. (Friedman and Taub)

In regards to placebos, there are significant differences between individuals and between types of placebos and what conditions they are being used for but, in general, the placebo effect successfully treats around thirty-five percent of patients. (Beecher)

Integrative medicine is starting to receive serious scientific study. These treatments have demonstrated therapeutic effects that appear to be equal to placebo. (Singh and Ernst)

There may be an underlying connection between all forms of non-pharmacologic intervention. It may be that the fundamental elements that are responsible for these effects can be elucidated and the individuals most likely to respond identified. Past confusion over these interventions may have been due to difficulties with definitions. We suggest using the term “Non-Pharmacological Intervention (NPI).” We further recommend a search for commonalities that would unify these interventions into a single therapeutic category. Then, we can both maximize and individualize treatment more effectively.

Psychotherapy

CBT- Symptom improvements with cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy correlate with blood flow and metabolic changes in the brain. (Goldapple et al) (Linden) (Prasko et al) (Lackner et al)

CBT is a form of talk therapy that is usually brief and time limited. The first goal is to correct dysfunctional behaviors. For example, a fear of cats can be ameliorated with activities such as extinction or over-exposure to cats in a calm and reassuring environment. These behavioral interventions are combined with cognitive restructuring. For example, a depressed person might think that because he or she was not selected for a role in the school play that they are un-loved and life is hopeless. The therapist facilitates the patient to take this type of thinking to its logical extreme. After repeated sessions the patient is able to understand that this thinking is irrational. CBT has demonstrated reliable and reproducible success in clinical trials. (Gould et al)

Major depression has been shown to improve significantly when treated with CBT alone and this improvement correlates with metabolic increases in the hippocampus and dorsal cingulate gyrus and decreases in dorsal, ventral, and medial frontal cortex. (Goldapple et al)

Obsessive-compulsive disorder also responds favorably when treated with CBT alone and several studies show decreased metabolism in the right caudate nucleus. (Linden)

Panic disorder also responds well to CBT alone and metabolic changes in the brain in one study included decreases in the inferior temporal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus of the right hemisphere and increases in the inferior frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and insula of the left hemisphere. (Prasko et al)

Irritable bowel syndrome also responds to CBT alone and one study found that neural activity in the parahippocampal gyrus and inferior portion of the right cingulate were reduced. (Lackner et al)

IPT- Interpersonal psychotherapy has also demonstrated blood flow and metabolic brain changes in depressed patients who respond to treatment. (Martin et al) (Brody et al) IPT combines psychodynamic principles and cognitive-behavioral approaches. It is brief, time-limited, and focused on the here and now. The four main areas that are stressed include grief and loss, conflicts with significant others, changes in purpose and identity, and interpersonal deficits.

IPT has been shown to be an effective treatment for major depression. (Weissman and Markowitz) Treatment responders demonstrate increased limbic and basal ganglia blood flow (Martin et al) and normalized prefrontal and left temporal metabolism. (Brody et al)

The mechanisms of CBT and IPT involve significant doctor-patient relationship factors. They also enlist patient cooperation and learning to master their techniques. The brain changes seem to be disease specific even if the non-pharmacologic healing factors are similar.

(It is important to point out that the combination of psychotherapy plus medication has generally been shown to be more effective than either alone.) (TADS)

Hypnosis

Hypnotherapy involves significant doctor-patient relationship factors. It works best when the patient is fully informed and it is not possible to get a patient to do something under hypnosis that the patient does not want to do. The patient willingly gives up their personal autonomy and follows the suggestions of the hypnotherapist. It is a collaborative effort between therapist and patient as the focused concentration of the trance state enables the patient to do something that was difficult to accomplish otherwise.

Analgesia is probably the easiest to study medical application of hypnotherapy and the only one that has been studied with functional brain imaging. Hypnotic modulation of pain can be very effective (King et al) and one study showed that the hypnotic state induced a significant metabolic activation of the anterior cingulate cortex. (Faymonville et al)

Placebos

A sugar pill is the classic placebo but many factors affect its saliency. For example, if it’s supposed to be a stimulant, then it will work better if it is red. If it’s supposed to be a sedative, then it will work better if it is blue. Two pills work better than one pill. A large pill works better than a small pill. A brand name pill works better than a generic pill. A pill that tastes bad works better than one that tastes good. Injections and medical devices work even better than pills.

Many would argue that suggestion, expectancy factors, and/or the doctor-patient relationship are the essential elements. In fact, when the doctor expresses warmth, attention, and confidence as the placebo is administered eighteen perecent more patients respond positively. (Kaptchuk et al)

Major depression improves with placebo therapy and this improvement correlates with functional brain changes. Preliminary evidence suggests that the pre-frontal functional deficit associated with depression improves with placebo treatment and that the limbic-paralimbic area experiences a functional decrease with successful treatment. It appears that these effects are similar but not identical to the effects associated with pharmacotherapy. (Mayberg et al) (Leuchter et al -2008) (Leuchter et al -2002)

Analgesia can be induced by placebo and this effect is mediated by the endogenous opioid system. (Levine et al) Functional imaging studies reveal that anterior cingulate cortex in the pre-frontal region and periaqueductal grey in the brainstem both increase activity secondary to placebo. (Wager et al) A follow-up study also found activation in the orbitofrontal and insular cortices, nucleus accumbens, and amygdala and dopaminergic activation in the ventral basal ganglia. (Scott et al) In this study, nocebo was compared to placebo. When patients were given nocebo they demonstrated reduced activation in the same areas that were activated by placebo. (Scott et al)

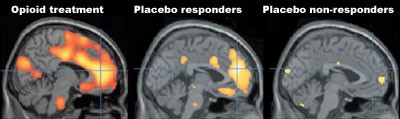

Opioid medications and placebo have a similar but not identical effect on endorphin pathways. (Petrovic et al)

NPI

(Petrovic et al.)

Parkinson’s disease patients responding to placebo demonstrate increased dopamine in the dorsal striatum, as do Parkinson’s patients responding to L-Dopa therapy. Interestingly, Parkinson’s patients treated with placebo also produce increased dopamine in the ventral striatum regardless of whether their symptoms improve or not. The dorsal striatum is associated with Parkinson’s disease but the ventral striatum is associated with expectation and reward mechanisms. (De la Fuente-Fernández et al -2006) (De la Fuente-Fernández et al -2004)

Integrative medicine

As a placebo, needles may be more salient than a large, red, and bad tasting sugar pill. However, like the sugar pill, doctor-patient relationship factors and expectation may play a more important role.

Acupuncture can be an effective analgesic and patients who respond also demonstrate changes on functional imaging in both the lateral and medial pain networks. (Dougherty et al) Acupuncture has been demonstrated to be about as effective as placebo (Linde et al) but functional brain changes associated with acupuncture analgesia are not identical to those associated with placebo analgesia. (Kong et al)

There are many other forms of integrative therapy but to my knowledge none of them have been studied with functional brain imaging.

Conclusion

There are both commonalities and differences in brain changes in individuals receiving non-pharmacologic intervention versus pharmacologic intervention, in individuals receiving different forms of non-pharmacologic intervention, and for individuals receiving treatment for different conditions.

Possible explanations include: (1). Medications are exogenous and tend to affect brain systems in a “shotgun” manner. Therefore, you would expect that imaging studies would detect activity related to treatment effect as well as random activity unrelated to treatment effect. (2). NPIs employ endogenous brain systems so you might expect that they would target the impaired area more specifically. You might also expect that they would enlist neuronal systems related to the organization of the therapeutic effect and this might be different with different NPIs. (3). Because the brain is able to correctly target the correct area to treat a specific condition, imaging studies that use the same NPI for different conditions cause condition-specific functional changes.

We think that psychotherapy, hypnosis, placebo treatments and integrative therapies share certain aspects that facilitate these brain changes. If we lump these modalities together and search for common elements then we could create a new therapeutic category that would truly compliment medical practice.

It is widely believed that placebo treatments require deception in order to work. No study has ever demonstrated this notion to be accurate. On the contrary, it has been shown that placebos can be effective even if the subject is aware of their nature. (Park and Covi) We believe, based on experience with psychotherapy and hypnosis, that a fully informed patient whose assistance is enlisted in the therapy will have a superior outcome.

Research on NPIs has a dubious history. Definitions have been confusing and research goals have had ulterior motives. Recent reviews of the “placebo effect” have focused on improving clinical trials, maximizing expectation effects when using active treatments, and generally understanding the neurobiology of opioid, dopaminergic, and serotonergic systems when exposed to a non-pharmacologic intervention. (Diederich and Goetz) (Oken) (Kupers et al) (Vallance) (Cavanna et al) (Beauregard)

We are suggesting that NPIs should be grouped together and studied in their own right. Real-time functional MRI has demonstrated that individuals given appropriate training can gain voluntary control over activation in a specific brain region that relates to analgesia. (deCharms et al) We think that the “appropriate training” in this study was not dissimilar to the essential therapeutic elements involved in a range of NPIs. It may be possible to educate and train informed patients in order to maximize treatment effect. Also, this would eliminate ethical concerns.

There are several criticisms to the suggestion that we lump all NPIs into a single category and integrate them into mainstream medicine based on an understanding of neurobiological mechanisms. First, it is not clear if the changes seen on imaging studies are due to NPI or simply due to the natural evolution of the disease process. Second, the relationship of electrical cordance, metabolic activity, and blood flow to underlying brain activity is not entirely clear. Third, if these treatment effects using NPIs have real neurobiological mechanisms, then we should be able to demonstrate more robust efficacy.

The idea that non pharmacologic interventions can cause real brain changes that correlate with real symptom improvement leads us to several recommendations. First, we recommend the creation of a new therapeutic category called NPI and we suggest that this definition better lends itself to scientific inquiry. Second, we would like to see research aimed at finding the essential non-pharmacologic elements common to all these modalities that produce clinical improvement. Third, we would also like to see research aimed at finding patient characteristics that predict clinical response. Finally, we would like to see NPIs integrated into mainstream medicine in a more appropriate way.

References

Beauregard M. Effect of mind on brain activity: Evidence from neuroimaging studies of psychotherapy and placebo effect. Nord J Psychiatry. -2008 Nov -20:-1-12.Beecher HK. (1955) The powerful placebo. J Am Med Assoc. -159(17):-1602-6.

Brody A.L., Sanjaya Saxena, Paula Stoessel, Laurie A. Gillies, Lynn A. Fairbanks, Shervin Alborzian, Michael E. Phelps, Sung-Cheng Huang, Hsiao-Ming Wu, Matthew L. Ho, Mai K. Ho, Scott C. Au, Karron Maidment, and Lewis R. Baxter, Jr Regional Brain Metabolic Changes in Patients With Major Depression Treated With Either Paroxetine or Interpersonal Therapy: Preliminary Findings Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2001);-58(7):-631-640.

Carroll, Robert Todd- The Skeptic’s Dictionary – A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions by (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, -2003)

Cavannaa , Andrea Eugenio,b Gionata Strigaroa Francesco Monacoa Brain mechanisms underlying the placebo effect in neurological disorders Functional Neurology (2007); -22(2): -89-94.

Christakis, N.A., and Fowler, J.H. The spread of obesity in a large social network over thirty-two years. New England Journal of Medicine (2007), -357(4):-370-379.

Daniel E. Hall, MD, MDiv. Religious Attendance: More Cost-Effective Than Lipitor? The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine -19:-103-109 (2006).

deCharms, R. C., Maeda, F., Glover, G. H., Ludlow, D., Pauly, J. M., Soneji, D., Gabrieli, J. D., & Mackey, S. C. (2005). “Control over brain activation and pain learned by using real-time functional MRI”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA.

De la Fuente-Fernández R, Lidstone SC, Stoessl AJ. The placebo effect and dopamine release. J Neural Transm Suppl. (2006);(70):-415-8.

De la Fuente-Fernandez R, Schulzer M, Stoessl AJ. “Placebo mechanisms and reward circuitry: clues from Parkinson’s disease.” Biological Psychiatry. (2004) Jul -15;-56(2):-67-71.

Diederich, Nico J., MD and Christopher G. Goetz, MD, FAAN NEUROLOGY (2008);-71:-677-684 The placebo treatments in neurosciences New insights from clinical and neuroimaging studies.

Domangue, B.B., Margolis, C.G., Lieberman, D. & Kaji, H. (1985). “Biochemical Correlates of Hypnoanalgesia in Arthritic Pain Patients.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, -46, -235-238.

Dougherty DD, Kong J, Webb M, et al. (2008). A combined -11C diprenorphine PET study and fMRI study of acupuncture analgesia. Behavioural Brain Research. Nov. (2008);-193(1):-63–68.

Eliezer Schnall; Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller; Charles Swencionis; Vance Zemon; Lesley Tinker; Mary Jo O’Sullivan; Linda Van Horn; Mimi Goodwin. The relationship between religion and cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in the women’s health initiative observational study. Psychology and Health. -17 November (2008).

Faymonville ME, Laureys S, Degueldre C, DelFiore G, Luxen A, Franck G, Lamy M, Maquet P Neural mechanisms of antinociceptive effects of hypnosis Departments of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine and Neurology, and the Cyclotron Research Centre, University Hospital of Liege, Liege, Belgium Anesthesiology (2000) May;-92(5):-1257-67.

Friedman, H. & Taub, H. (1978). “A Six Month Follow-up of the Use of Hypnosis and Biofeedback Procedures in Essential Hypertension.” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, -20, -184-188.

Giles, L. C., G. F. V. Glonek, M. A. Luszcz and G. Andrews (2005). “Effect of social networks on ten year survival in very old Australian: the Australian longitudinal study of ageing.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health -59:-574-579.

Goldapple K., MSc; Zindel Segal, PhD; Carol Garson, MA; Mark Lau, PhD; Peter Bieling, PhD; Sidney Kennedy, MD; Helen Mayberg, MD Modulation of Cortical-Limbic Pathways in Major Depression Treatment-Specific Effects of Cognitive Behavior Therapy Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2004);-61:34-41.

Gould, RA; Michael W. Otto, Mark H. Pollack, Liang Yap (1997). “Cognitive behavioral and pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary meta-analysis.” Behavior Therapy -28 (2): -285–305.

Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, Davis RB, Kerr CE, Jacobson EE, Kirsch I, Schyner RN, Nam BH, Nguyen LT, Park M, Rivers AL, McManus C, Kokkotou E, Drossman DA, Goldman P, Lembo AJ. (2008) Components of placebo effect: randomized controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. -336(7651):-999-1003. PubMed.

Kaplan R.M., Richard G Kronick Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (2006); -60:760-765; Marital status and longevity in the United States population.

King, Brenda J; Nash, Michael; Spiegel, David; Jobson, Kenneth. Hypnosis as an intervention in pain management: A brief review International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. Vol -5(2) Jun (2001), -97-101. Taylor & Francis, United Kingdom.

Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al May (2000). “A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression.” New England Journal of Medicine -342 (20): -1462–1470.

Kong J, Kaptchuk TJ, Polich G, Kirsch I, Vangel M, Zyloney C, Rosen B, Gollub R. Neuroimage. (2008) Dec (29). Expectancy and treatment interactions: A dissociation between acupuncture analgesia and expectancy evoked placebo analgesia.

Kupers R, Faymonville M-E, Laureys S The cognitive modulation of pain: hypnosis- and placebo-induced analgesia Progress in Brain Research, -150 (2005) -251-269.

Lackner JM, Lou Coad M, Mertz HR, Wack DS, Katz LA, Krasner SS, Firth R, Mahl TC, Lockwood AH; Cognitive therapy for irritable bowel syndrome is associated with reduced limbic activity, GI symptoms, and anxiety.; Behav Res Ther; (2006) May; -44(5); -621-638.

Leuchter AF, Cook IA, DeBrota DJ, Hunter AM, Potter WZ, McGrouther CC, Morgan ML, Abrams M, Siegman B. Changes in brain function during administration of venlafaxine or placebo to normal subjects. Clin EEG Neurosci. (2008) Oct;-39(4):-175-81.

Leuchter AF, Cook IA, Witte EA, Morgan M, Abrams M. Changes in brain function of depressed subjects during treatment with placebo. Am J Psychiatry. (2002) Jan;-159(1):-122-9.

Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL. Lancet. (1978) Sep -23;-2(8091):-654-7. The mechanism of placebo analgesia.

Linde K., MD; Andrea Streng, PhD; Susanne Jürgens, MSc; Andrea Hoppe, MD; Benno Brinkhaus, MD; Claudia Witt, MD; Stephan Wagenpfeil, PhD; Volker Pfaffenrath, MD; Michael G. Hammes, MD; Wolfgang Weidenhammer, PhD; Stefan N. Willich, MD, MPH; Dieter Melchart, MD JAMA. (2005);-293:-2118-2125. Acupuncture for Patients With Migraine: A Randomized Controlled Trial.

Linden DE. Mol Psychiatry. (2006) Jun;-11(6):-528-38. How psychotherapy changes the brain–the contribution of functional neuroimaging.

Martin S.D., Elizabeth Martin, Santoch S. Rai, Mark A. Richardson, and Robert Royall Brain Blood Flow Changes in Depressed Patients Treated With Interpersonal Psychotherapy or Venlafaxine Hydrochloride: Preliminary Findings Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2001);-58(7):-641-648.

Mayberg HS, Silva JA, Brannan SK, Tekell JL, Mahurin RK, McGinnis S, Jerabek PA. The functional neuroanatomy of the placebo effect. Am J Psychiatry. (2002) May;-159(5):-728-37.

Montgomery G.H., PhD*, Daniel David, PhD*, Gary Winkel, PhD*, Jeffrey H. Silverstein, MD , and Dana H. Bovbjerg, PhD The Effectiveness of Adjunctive Hypnosis with Surgical Patients: A Meta-Analysis * Anesth Analg (2002);-94:-1639-1645.

Oken, Barry S. Placebo effects: clinical aspects and neurobiology Brain (2008) -131(11):-2812-2823.

Park LC, and Covi L: Nonblind Placebo Trial Arch Gen Psych -12(1965):-336-44.

Petrovic P, Kalso E, Petersson KM, Ingvar M, Placebo and Opioid Analgesia- Imaging a Shared Neuronal Network SCIENCE VOL (2950 (1) MARCH (2002) -1737-1740.

Prasko J, Horácek J, Záleský R, Kopecek M, Novák T, Pasková B, Skrdlantová L, Belohlávek O, Höschl C. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. (2004) Oct;-25(5):-340-8. The change of regional brain metabolism (18)FDG PET in panic disorder during the treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy or antidepressants.

Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatuk CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Placebo and nocebo effects are defined by opposite opioid and dopaminergic responses Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2008) Feb;-65(2):-220-31.

Simon Singh and Edzard Ernst, MD Trick or Treatment: The undeniable facts about alternative medicine W.W. Norton & CO., New York (2008).

(TADS) Fluoxetine, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, and Their Combination for Adolescents With Depression Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Randomized Controlled Trial Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Team JAMA. (2004);-292:-807-820.

Vallance, Aaron K. A systematic review comparing the functional neuroanatomy of patients with depression who respond to placebo to those who recover spontaneously: Is there a biological basis for the placebo effect in depression? Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume -98, Issue (1)-(2), February (2007), Pages -177-185.

Wager TD, Scott DJ,Zubieta JK. Placebo effects on human µ-opioid activity during pain. PNAS (2007);-104:-11056-11061.

Weissman MM, Markowitz JC. Interpersonal psychotherapy: current status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1994);-51:-599-606.

Whorwell PJ; Prior A; Faragher EB. Controlled trial of hypnotherapy in the treatment of severe refractory irritable-bowel syndrome.The Lancet (1984), -2: -1232-4.

Register to receive notification of new content.